Adam Williams ponders his family’s South African roots

At about the age of twelve I conceived a passion for Zulus and their history.

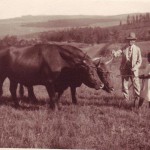

Figure 1: Henry Bernard Newmarch's farm, Wonderboom, in Greytown, Kwa Zulu, SA (Courtesy of Mrs Belinda Pascal)

By then I had read most of the Allan Quatermain novels by Sir Henry Rider Haggard and I loved them all. There were great adventures about lost cities and savage kingdoms, witch doctors, wars, monstrous animals and more monstrous humans, but the stories that moved me most were those in which Haggard’s great white hunter became involved in Zulu history. I was captivated by the Zikali trilogy: Marie, in which Allan found a wife on the Boers’ Great Trek and fell foul of the treacherous Zulu king, Dingane; Child of Storm, the story of the Zulu femme fatale, Mameena, who in Haggard’s romance caused the civil war between the sons of King Mpande that led to the dreadful slaughter at Ndondakasuka (the Zulu equivalent of Gettysburg); and the tragic finale of the trilogy, Finished, in which Allan cannot prevent war with the British and sees the fall of the Zulu nation. My hero, though, was not really Allan Quatermain, but rather his Zulu companion, Umslopogaas – a noble warrior, bastard son of the great king Shaka, who wielded the axe, Inkosi-kaas, and whose life is told in three volumes, Nada the Lily, Allan Quatermain (perhaps Haggard’s most touching novel) and the strange She and Allan, in which the pair stray into the territory of Haggard’s greatest heroine, the mysterious and magical Ayesha, or She Who Must Be Obeyed.

I lived then in Hong Kong, a colourful city that in the Sixties was as adventurous and exotic a location as any little English boy might desire. It was a childhood of launch picnics on the then unpolluted South China Sea, or excursions to the nearby Portuguese enclave of Macau, where we stayed in the old Bella Vista Hotel with its balconies hanging over the Praya, looking down over the junks that were moored in the yellow water of the Pearl River Estuary, with excursions to bull fights and curio shops and nights at the trotting track with gangster friends of my father. And always there were the markets, where an exotic China screamed in Cantonese from the fish stalls and temples, and rickshaws pulled mysterious men and women in cheongsams and dark spectacles to the gaming halls. Just standing and looking about one was exciting – but I was always impatient of these distractions. I wanted to get back to my air-conditioned bedroom and sink myself into the pages of Marie or King Solomon’s Mines. THAT was the world that enchanted me: the veldt, the blue-tinted mountains, the savage tribes, the magic and wonder of an Africa of the imagination.

Romance led me to history – Donald R Morris’s The Washing of the Spears, E A Ritter’s Shaka Zulu, Stephen Becker’s Rule of Fear (where I found that the real facts about the terrible Dingane were more dramatic than in Haggard’s novel), and by the time I got to my public school I was more knowledgeable about Zululand than Britain. I embarked on a major project, filling 50 pages with typed facts and pictures about all aspects concerning the Zulu nation and its wars. I built balsa wood models of the mission station at Rorkes Drift (of course I loved the movie, Zulu, which I could quote by heart) and I also constructed in my step-grandfather’s garage in Sussex a papier mache model of a Zulu kraal. At the age of 14, I was giving lectures on Zulus to my fellow pupils (I think they were a success because I took care to go into great detail about the art of uku Hlobonga, or Fun of the Roads, a form of accepted sex play, misapplication of which led the Zulu Prince Senzanzakona to father a child on a maiden he had met by a stream – with terrible consequences, because the “i-shaka beetle” that swelled to her shame in Nandi’s belly became the despotic warrior, Shaka, whose vengeance on the world brought the Zulu nation greatness at the cost of millions of lives .. Oh yes, I knew how to fire my friends’ imaginations and there were few details of Zulu life and lore that did not add fuel and colour to my presentations.)

Naturally I conceived a desire to travel to South Africa and visit Natal and Zululand and see for myself all the great sites whose geography and topography I knew as well as that of the downs over which I wandered when I stayed with my grandmother during school holidays – the great kraal at Ulundi, the battlefields of Isandhlwana and Hlobane, and of course, the old mission station at Rorkes Drift. Close my eyes and I could imagine every shade of hill and kopje – but I wanted also the smell, the feel of a hot wind in my face, and the triumphant knowledge that I was standing where once might have trod my childhood companions, Umpslopogaas, Hans the Hottentot and Allan Quatermain.

Nothing came of it. My life followed a different course. I ended up in China where I am still today. Forty years have passed but I never entirely abandoned my African dream. Whenever anything to do with South Africa – especially Zulus – came into conversation, my ears pricked up. I developed a more adult understanding: of Apartheid and sanctions, of de Beers and the ANC, of the struggle for Independence and Zulu politics of today. I still read Zulu histories as they come out. Five years ago, perusing Saul David’s, “Zulu: The History and Tragedy of the Zulu War” I was startled to see he had quoted a “Natal settler” called T.E. Newmarch, who had interviewed “an iNgobamakhosi warrior” about Zulu tactics at the battle of Isandhlwana. Newmarch was of course my mother’s maiden name. How nice it would have been, I thought fondly, if the Newmarch quoted had been somehow related to my family; then I would have had a connection with Zululand that might somehow justify my inexplicable passion for that country I had never visited – but I knew that such coincidences just don’t exist.

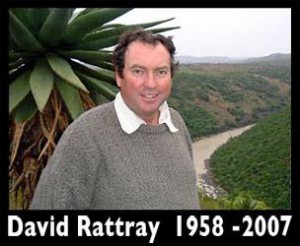

One day I heard of David Rattray, the historian who actually lived in Rorkes Drift and organised tours of the battlefields. I pledged to myself that one day I would join one of those tours. I learned he was speaking in Hong Kong at the Royal Geographical Society. I was immediately tempted to fly down, but then I told myself, no need, soon you’ll be there in person. Two months later I read the tragic news that Mr Rattray had been murdered on his farm. I listened in sadness to his wonderful personal and virtuoso oral history of the Zulu wars, a set of five CDs under the title Day of the Dead Moon, and I mourned a stranger with whose passing seemed to evaporate my fantasies. Thinking of his tragic death, at the hands of the Zulus whom he had loved and helped and who paid him back so cruelly, my romantic fascination appeared to me naïve, a boyhood folly. I believed that a chapter in my life had closed. I thought that at last I had got over my childhood infatuation.

Then last year, out of the blue, I received an email from Kwa Zulu.

Discovering my African roots

I have already written a little about my family origins in China. Last year, on this website, I attached an article that described how I had discovered an unknown past when a stranger called Philip Coetzee wrote to me saying he had information about my grandfather who after the Second World War had disappeared out of our lives to the town of Cradock in the Eastern Cape. Subsequently distant relatives – who had also discovered me on the internet – wrote to me filling in different parts of my family history, enough for me to speculate how my family ended up in South Africa. (See Adam Williams finds family secrets through his website).

According to the story I had worked out, based on wisps of fact, my great grandfather, Leonard Newmarch, stopped off in South Africa on his way to China sometime in the early 1890s. I decided he had gone to visit his brother, Henry Bernard Newmarch, who, some years previously, bruised after a hopeless love affair, had settled on a farm in Greytown, which, in my ignorance, I believed was somewhere in the Eastern Cape Province, close to Cradock, the home of the South African girl, Sadie Newmarch, who became Leonard’s wife and my great grandmother (Philip Coetzee had learned that she came from a long line of Biddulphs who had emigrated to this part of South Africa way back in the 1820s.) Obviously, I thought to myself, counting two and two and making five, Leonard met this girl when staying with his brother in Greytown. The theory seemed to make sense. Where else could they have met? Cradock had some sentimental value for them. It was there Leonard and Sadie retired in 1927 from China and it explained why after the war my grandfather retreated there after his divorce from my grandmother. I had filled in the facts to my satisfaction and thought no more about it. My family’s South African connection was anyway only a mild and tangential interest in my attempts to find out more about my family in China. And the Eastern Cape (I had not then read the amazing book Frontiers by Noel Mostert about the Kaffir Wars of the early Nineteenth Century) held for me none of the romance of Natal. There were no Zulus there!

I put it out of my mind – but one early January day last year I came home to find I had another unsolicited email, this time – unbelievably – from a Newmarch who lived in Greytown! Mr Mike Newmarch had seen my article, he said, and being a keen genealogist, realised that we were related. Later his son, Peter, also a keen genealogist, entered the correspondence.

And it was only then that I discovered my ignorance and stupidity. Henry Bernard Newmarch had not gone to South Africa on a whim. He went to Greytown because he had family there already. Mike Newmarch confirmed it. Studying the photo of HBN’s farm that I sent him, he identified it as Wonderboom, a property that had originally belonged to Mike’s own father and his Uncle Jack. He even remembered his family talking about HBN. He had the nickname ‘Ostrich.’ That probably meant he farmed ostriches as well as cattle.

And – here was the fact that thrilled me to my bone marrow – Greytown, where HBN settled, was nowhere near Cradock in the Eastern Cape, as I had foolishly conjectured (next time I’ll look at an atlas before I start coming to daft conclusions!). It was thousands of miles up the coast. It was in Kwa-Zulu! Zululand! Members of my family had lived in Zululand! And from what Mike and Peter told me, they had done so for more than a hundred years. Blood relations of mine had actually played a part in the history that I had spent my boyhood dreaming about!

This was the message that Mike Newmarch sent me:

“The Newmarch Family tree that I have is on a massive sheet of paper approx. 1metre x .8 Metre and I am in the process of scaling down your family tree to fit A4 sheet.

It will start with John 1748 who was the father of Henry the Parson at Hessle who was your great,great,great grandfather and William my great, great grandfather.As soon as I have completed it I will e-mail it to you.

My family came to the Greytown area in 1849.They were the 4 sons of William namely

John 1829

Thomas Browne —-

George William 1832

Edward Sawdon 1834

Thomas was killed by a Rhinoceros near Durban. John went on to Fiji and then eventually settled in Australia. Edward Sawdon remained a bachelor. All the Southern African Newmarch’s are descended from George William.”

Of course the link was tenuous – it was a great, great, great, great grandfather we shared, after all. But never mind, my ancestor, ‘Henry the Parson’ – The Rev. Henry Newmarch (1801-1883), the vicar of Hessle, who fathered my line of the family, through his son John (1832-1906), and then his son, Leonard John (b. Hessle 1867 d. Cradock, SA, 1953), and later his son Guy Lumley Biddulph (b. in China 1896 d. Cradock, SA, 1964) and finally his daughter Anne Catherine, my mother (b. China 1927 d. London 1990) – was the brother of the patriarch of a South African Dynasty, William, whose sons, in 1849, in the time of the Zulu King Mpande, had uprooted themselves from Yorkshire to Natal Colony!

It was a marvellous revelation. Within hours of receiving his father’s first email, I was in correspondence with Peter Newmarch about “the Natal settler,” T.E. Newmarch, who had been involved in the Zulu War.

Well, it was a little disappointing, since Peter believed that the ‘E’ was a mistake and the man being referred to was a T. H. Newmarch, who was born nine years before the Battle of Isandhlwana and so his conversation with the “iNgobamakhosi warrior” must have taken place years after the event – but it was still a connection for all that. The matter is not yet cleared up. There is research to do. Peter believes the documents quoted are probably located in the Killie Campbell Library in the University of Natal. So a visit is in order one day. It anyway doesn’t prove that members of the Newmarch clan DIDN’T take part in the Zulu War.

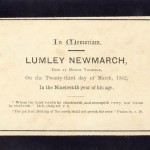

Figure 5: The Rev Henry Newmarch, Vicar of Hessle, Yorks, my ancestor and brother of a South African dynast (photo courtesy of Mike and Peter Newmarch, Greytown, Kwa Zulu, South Africa)

Meanwhile there has been an even more exciting development. Peter wrote me just a few days ago to say that he and his father have discovered a family vault of memorabilia:

“Photos, letters, newspaper clippings etc.. etc.. I guess about 100 – 200 letters and many, many photos (I guess about maybe 300 old photos or more) all from mid 1800’s through to the 1940’s….”

He sent me a copy of one photograph as a sampler. It was of my great, great, great grandfather, his great, great, great, great uncle, Henry Newmarch, Vicar of Hessle.

Looking at the photo I felt an enormous sense of pathos and experienced another revelation. The vicar is standing by a grave marked Lumley, his son who died as a child. I had never known why my grandfather had a Lumley in his name. Now I did. Leonard, his father, my great grandfather, was remembering a brother who had passed away. Also, looking closely at the photo there was another surprise: my great, great, great grandfather has the same features as me. All I would need to look like him would be a set of white whiskers!

It will take years perhaps for the Greytown Newmarches to investigate thoroughly their treasure trove, but certainly it is a major find, and will give the whole extended family much information about our shared origins.

The Eastern Cape connection

Meanwhile, I was continuing to receive new information about that other pocket of my family: those who settled in Cradock, in the Eastern Cape.

Another stranger who had seen my website contacted me. (I really must put a disclaimer, by the way, on any claims to be a genealogist. I have done NOTHING except sit and receive emails!). This latest benefactor was Dr Anton Moolman, from Cradock. I had heard of the Moolmans from Philip Coetzee. They were friends of my great grandparents and knew my grandfather as the Coetzees did, but Philip did not have an address to contact them. The magic of the internet saved him the trouble. For Dr Moolman found me!

And there was gold dust in his message, for he was able to tell me about how my great grandfather, Leonard, and my great grandmother, Sadie, met.

Now I had already discovered from my friend, Peter Crush, an expert on the China Railways who lives in Hong Kong, a little about what had brought my grandfather to South Africa. China Railways records showed how Leonard, after working for four years on the Hull and Bolton Railway in northeast England, went off in 1890 to join the Cape Government Railway as an Assistant Engineer.

This, by the way, made nonsense of my speculations in my last article, that Leonard went to South Africa because his brother Henry Bernard was there already. In fact Leonard arrived in South Africa eight years before his brother, and a thousand odd miles to the south!

But it placed Leonard in the early 1890s in Cradock, because that was a town the Cape railway passed through, and it seemed to clinch the question of how he met his future wife, my great grandmother, Sadie Biddulph. Dr Moolman was able to confirm it:

Figure 6: My great grandfather, Leonard "Jack" Newmarch, in N China c. 1919 (Photo Reproduced from the P.A. Crush Chinese Railway Collection and with the kind permission of the grandchildren of Claude William Kinder C.M.G.)

“My parents told this story of how Leonard (Jack) met Sadie: When the railway line was built between Port Elizabeth and Noupoort there was a British engineer by the name of Newmarch working on the railway line. When the railway reached Cradock, the engineer met a beautiful lady by the name of Sadie. He fell in love with her. ……When the railway line was completed Newmarch was privately engaged to Sadie and together they went to England. Apparently his parents did not like the colonial girl, thinking that she was not blue blooded enough. Newmarch was furious and married Sadie and promptly went to China where he joined the Chinese Railroad.”

This was fascinating to me. I never knew that Leonard was nicknamed Jack. And nor did I know that his marriage to Sadie caused something of a family scandal (rather a tradition, it seems, in the Newmarch family: as my previous article relates, Leonard’s parents eloped, his mother’s sister married his father’s brother, and his brother’s sweetheart was not allowed to marry him because she was a first cousin! Rather shamefacedly I remembered my own first marriage, which I had conducted in secret in Taiwan because I thought my parents might disapprove. Obviously I had inherited the impulsive Newmarch genes!)

But the proud Newmarches of Hessle had no right to look down on Sadie. Her family, the Biddulphs, were something in the way of being South African gentry. Originally from Tamworth in the County of Stafford, they were “Cousins of Sir Theophilus Biddulph of Birbury in the County of Warwick, Baronet.” Several Biddulphs came out together as part of the Baillie Party (famous among Eastern Cape settlers – see http://www.genealogyworld.net/nash/bailie.html ), sailing out of Deptford in 1820 on the ship ‘Chapman.’ Sadie’s grandfather, Midshipman John Burnett Biddulph, aged 23, was one of them. They arrived in Algoa Bay and moved to Grahamstown just in time for the Kaffir Wars, and later settled all over the area, with big estates from Bathhurst to Cradock. Sadie’s father, Edward, was a landowner in Cradock.

I guess it was more likely something about Sadie’s wild beauty that startled the staid Newmarches in Hessle. I have no photograph of her, but all my mother’s stories about her grandmother was of somebody grand and imperious and (strangely) “Irish” (although that connection has yet to be explained!). Dr Moolman, who knew her in her declining years, after she and her husband had retired from a lifetime in China to Cradock, told me how much she had impressed him as a child: “I don’t know how my parents got to know the Newmarches. As a child I was aware of the fact that my father, whenever he went to town, always had a box of vegetables and meat for the Newmarches which he delivered to their house. We lived on a farm about 25 miles outside Cradock . I was born in 1937 and therefore knew the Newmarches as well as a boy can know them. ….. I can remember Sadie as a very beautiful older lady.”

Reading these words I felt a strange sensation of time telescoping.

***

I am finding e that my interest is now broadening beyond the boyhood romance with Zulus. Over this last year, I have been reading more and more about the Eastern Cape, which has a history I find just as dramatic (and tragic) as Natal’s. I have mentioned the book ‘Frontiers’ about the Kaffir Wars and the defeat of the Xhosa people. It is as grand a masterpiece as The Washing of the Spears.

Also, as a Christmas present I was sent (by South African friends in Hong Kong) an extraordinary diary, written by a young (and very precocious) little girl, called Iris Vaughan. Gloriously mis-spelt, it describes her life in Cradock at the time of the Boer War.

And reading her words and looking at the photos taken more than a hundred years ago, I was able to recreate in my mind in colourful detail the sights, sounds and even the smells of the small agricultural town near the Great Karoo desert in which my great grandparents met.

I see the huge Cape ox-carts trundling down the white roads, farmers on horses raising their hats to ladies in bonnets, I hear the tinkle of a piano from the hotel, and the laughter of children playing in an orchard full of fruit – one of whom is the mischievous Iris Vaughan, the judge’s daughter, whose wild upbringing was no different to that of my great grandmother Sadie, ten years her senior.

My discovery of a family past of which a year ago I knew nothing has revived all my desires to travel to South Africa, certainly to visit the Zulu battlefields, but also now to visit the places associated with the Newmarches and Biddulphs, and perhaps even to meet extended members of my family, who – unlike me – have always known that beautiful country as home.

Notes: Books mentioned in this article

My thanks to friends and family on the internet who have ‘written to me out of the blue’: Philip Coetzee, Mike and Peter Newmarch, Dr Anton Moolman, Belinda Pascal, Jane Wynne, Paul Dunham, Peter Crush and Wendy Fenton-